Society has a fascination with lists and rankings, and the Forbes 30 Under 30 has become a modern-day representation of the Social Register in the entrepreneurial world. With recent high-profile failures and legal issues involving some of these Forbes 30 Under 30 recipients, it begs the question: Does this list truly signify success, or is it simply a starting line for entrepreneurs?

Is the Forbes 30 under 30 a good investment vehicle?

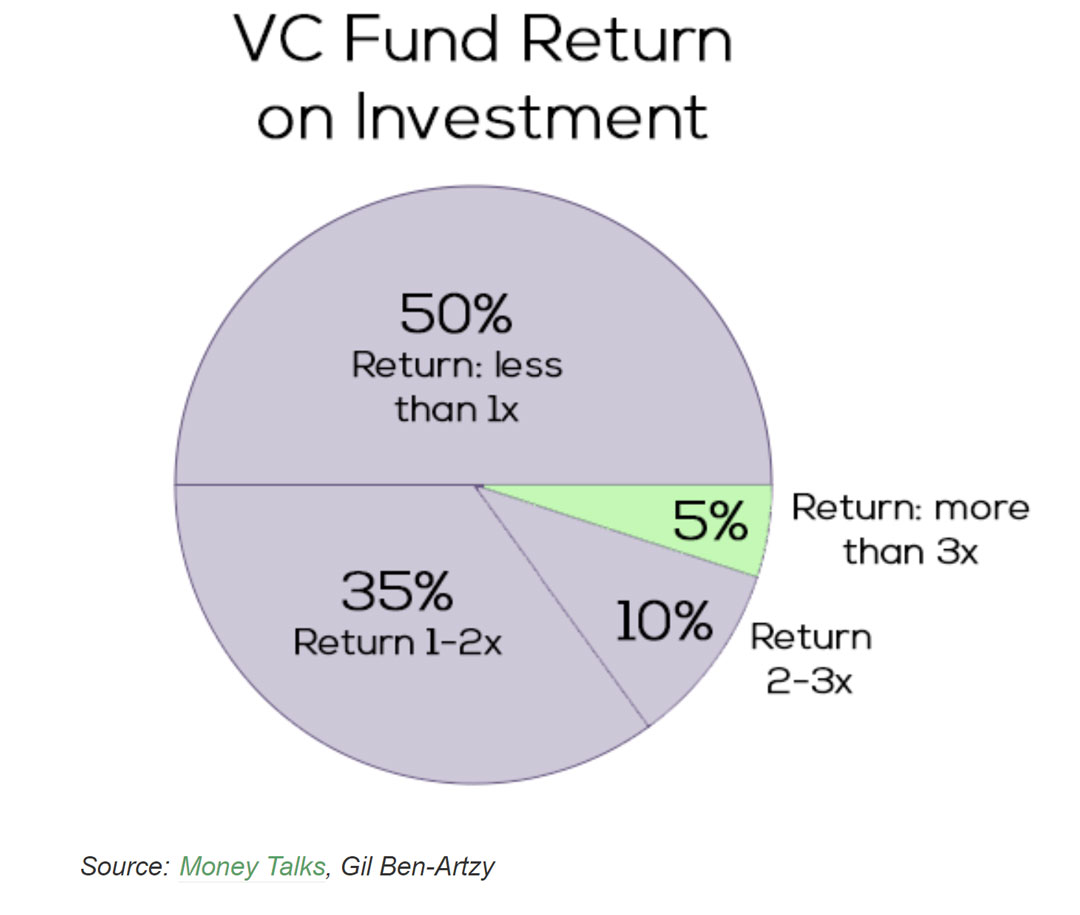

This is not a post about the founders who have gone to jail or have been indicted for fraud (maybe that is a future post). Instead, I analyzed eCommerce founders who were named to the Forbes 30 Under 30 list between 2012 and 2022 to understand the impact of this recognition on their companies’ success. According to the traditional venture capital (VC) rules of thumb, out of 10 companies, half will fail, four will return your money, and one will be a runaway success. I wanted to know what returns you’d expect if you had invested $1 million into each CPG startup at their next available round after a founder was named to the Forbes 30 Under 30 list.

I’ll start off by saying that this is an approximate calculation meant to provide a rough summary versus hard metrics (insert commentary about how crunchbase is inaccurate and pitchbook being crazy expensive to get this data).

We looked at close to 200 CPG and CPG adjacent companies (think deliveries & fulfillment), but only evaluated 34 whose crunchbase data appeared to be accurate. Out of the 34 companies reviewed, all but 1 was still active, and 2 had been acquired or gone public.

Using publicly available data we found the valuation for the next raise and calculated our percent ownership if we had put in $1M at that valuation. From there we counted the number of raises from that period to now and assumed 30% dilution with each round with no follow-on investment from our side. We then calculated our new ownership stake and multiplied it by the most recent public valuation to determine what our stake was now worth.

Even though this was a small sample size, there were a handful of companies and “investments” that stuck out to me.

Our Big winners

- Go Puff (Class of 2017) ~ 305x Paper Return

- Deliverr (Class of 2019) ~101x Actual Investor Return (Acquired by Shopify for $2.1B)

- Glossier (Class of 2015) ~ 57x Paper Return

- The Farmer’s Dog (Class of 2017) ~ 35x Paper Return

- LOLA (Class of 2016) ~20x Paper Return

- Casper (Class of 2015) ~ 15x Actual Investor Return (IPO’d at $476M Market Cap)

- Care/of (Class of 2018) ~ 10x Actual Investor Return (Acquired by Bayer for $225M)

- Pair Eyeware (Class of 2021) ~ 11x Paper Return

- The Flex Company (Class of 2017) ~ 8x Paper Return

- Hawthorne (Class of 2019) ~ 6x Paper Return

Even if the rest of the entire portfolio of 200 companies we invested $1M in went to zero, the top 10 companies would have a combined value of $568M to $284M depending on the size of the valuation haircut we decided to realize. A 2.8X return would put us into the upper echelons of venture capital returns.

It’s interesting to note that the top two outcomes were in ecommerce enablement (logistics) which fetched tech valuations even though their businesses are focused on moving boxes instead of bits. The next two – true CPG companies – are category defining Unicorns and the rest of the cohort contains category creators and unique product innovations.

These made for great hypothetical investments because in most of these instances, valuations were relatively low when they made the Forbes list. Only 3 had valuations greater than $10M. $10M is virtually nothing in the fundraising world (some idea stage seed businesses raise SAFEs at this level). Being able to get in early enough makes even a modest exit appear amazing for an investor.

Some Standout Exceptions that didn’t make my list

I think it’s important to call out some companies that didn’t make my top 10 where I think Forbes really got the selection right. The pretext of the Forbes 30 under 30 is that they are finding the best entrepreneurs and companies from around the world. The following companies are totally against the profile of what we’d normally expect on the Forbes list.They are profitable, bootstrapped, and coincidentally both from Colorado.

Vitality (Class of 2022)- Founded prior to the pandemic and after weathering a lawsuit from New Balance that prompted a name change from Balance Athletica, Vitality has seen rapid revenue growth. The only money they raised was $117k from Uncle Sam- in the form of PPP loans and the trio of founders (all related) remain in firm control of the company.

BruMate (class of 2018)- I actually had the chance to meet their founder Dylan a few years ago and was impressed with how well he had built his business. He had strong unit economics, a resilient team, and uncanny operational excellence. The most amazing thing in my opinion, was that he was able to build a $100M virtually completely bootstrapped. In fact, their only investor is a private equity firm who purchased a stake, most likely to provide some liquidity to the founding team and help prepare the business for an eventual sale.

From the perspective of our hypothetical investment BruMate & Vitality were disqualified (they wouldn’t take our monopoly money), but I’d like to see more bootstrapped, fundamentally sound businesses from outside of the traditional venture hotspots included on the list in the future.

Why do these Companies perform well?

I think the secret sauce of the best performing CPG brands on my list was early stage capital efficiency. When you’re disciplined about what you will and will not spend money on when you don’t have a lot, you have to develop the ability to make decisions and say no to good ideas. Learning this early on, and prioritizing what really matters, makes all the difference when additional dollars are unlocked. Two companies I’ve worked with illustrate this point well- The Farmer’s Dog built out an incredible customer centric operation (they print out your dog’s name on each meal… at scale) while The Flex Company spent their first investment dollars on purchasing a defensible moat in the form of patented products and manufacturing assets.

Zeroing in on the founders themselves and reflecting on those on the list that I have a personal connection with, one thing that becomes apparent is how natural they are as salespeople and fundraisers. Most recipients excel at promoting themselves and their companies, which in turn makes them great CEOs. Some come with strong personal brands or the ability to capture media attention (like Emily Weiss of Glossier) or are adept at speaking VC because they came from an investment background (such as Jesse Horwitz of Hubble Contacts).

Another commonality I’ve seen is the founders ability to identify and capitalize on PR opportunities. Founders benefit from the exposure and publicity that comes with being named to the Forbes 30 under 30, which can help elevate their brands. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that many of the founders on this list closed another round of funding within a few months of being named. As much as anything, the Forbes 30 under 30 serves as an external stamp of validation for VCs of who to consider. If it’s not the deciding factor, it is at the very least a tie breaker or enough to warrant a meeting. Investing in founders on the list also provides cover for VCs with their LPs- even if the company is a bust it’s easier to justify the miss with LPs.

I think the last factor that helps explain the performance of companies after they are named on the list is around talent acquisition. If you take away the funding advantages between a company on the list and one off of the list, it’s much easier to convince people to join a startup that they’ve heard of versus one that is unknown. Everybody, especially first time startup employees, want to join something that is going to be successful and will propel their career forward. Seeing that a company has been listed on Forbes can at the very least serve as a tiebreaker between two equally good opportunities.

Is there a downside to being on the list

In some cases, this extra attention may actually be counterproductive for a brand enticing them to raise more money than they should and leading them to do things that perhaps they shouldn’t. A good example of this is the biggest winner, so to speak, in our hypothetical portfolio- GoPuff.

In 2017 when Yakir Gola was named to the Forbes 30 under 30 list GoPuff was a modest sized business that was centered around and catered to college dorms. Initially they were the go to app for vaping and alcohol but quickly expanded into late night munchies. The reality is that when someone was ordering from GoPuff they usually asked if anyone else in the dorm wanted something (and they usually did). This resulted in GoPuff having enlarged AOVs and an amazing order density that other carriers could only dream of. No wonder they were growing so fast!

In our hypothetical portfolio, our $1M investment at their next available valuation of $8.25M would have netted us 12% ownership stake.

GoPuff would go on to raise $3.6B in total, including $750M from Softbank during the height of the pandemic, expanding instant delivery in cities and internationally and extending its product line beyond the college staples into things like groceries. They spent roughly $700M in 2021 to fuel this expansion and acquire a few companies, but as economies started to open up and demand for instant delivery slowed down it revealed cracks in their strategy. Compared to the high AOV and order density they had enjoyed with college dorms, they were finding smaller basket sizes going to more stops which hurt their unit economics. Since late 2022 (18 months after the softbank investment), they’ve exited Europe, quit categories, raised fees to consumers, and layoffs have been a common occurrence as they grapple with how to right size their business.

As with most things in venture, hindsight is 2020. GoPuff probably shouldn’t have raised $3.6B in such a short period of time. I can’t fault the founders- I think you’d be hard pressed to find a 30 something year old in an echo chamber telling them they are awesome, with other people who are rushing to give you hundreds of millions of dollars, and who is personally looking at a liquidity event related to the raise who wouldn’t take the money.

There are several other examples on the list of Brands whose valuations soared only to come crashing down when they IPO’d or when the market turned which can make one conclude that VC’s don’t build businesses, they build valuations.

I have no idea how much money the founders and employees of GoPuff were able to take out in secondary sales (probably very little for the former group) or what percentage of the company they still retain after all of the dilution and payout preferences are considered, but one can’t help but to wonder if they would have been better off sticking with college dorms and owning a larger portion of a smaller business.

Does the Forbes 30 Under 30 matter?

All of this begs the question; Is Forbes the single best talent spotter in the world? Should they end their publishing business and just focus on startup investing? Not quite.

Yes, the Forbes 30 Under 30 matters, but it should be viewed as more of a kingmaker than a recognition of already-established success. It offers a head start but is not the definitive list of great entrepreneurs. The advantages are real (higher profile, talent acquisition & fundraising), but success is not limited to only venture-backed startups in specific locations or entrepreneurs born before a specific date (there is hope for us mid 30 year olds). I think the right way for us to look at the Forbes 30 Under 30 list is that it is a starting line, not a finishing line. It’s an audition to make the most of an opportunity with a good chunk of the ecosystem watching you, but ultimately success depends on all of the things that every entrepreneur will need to get right- building a business with good fundamentals while communicating a compelling vision of the future.